Contemporary photographers from Iran (guest blog by Manuela Klerkx)

I. The Magic Black Box

If the British Queen Victoria, in 1882, hadn’t offered a photographic camera to the Qajar Monarch, Mohammad Shah, and if his eleven year old son, Prince Nasereddin Mirza (1831-1896), hadn’t fallen in love with the ‘black magic box’, the story of Iranian photography would have been totally different. In fact, Nasereddin Shah - who considered himself a modern Monarch - made the first ‘selfie’, taking pictures of himself surrounded by his concubines, thus showing his power and wealth to the Western world.

Nasereddin Shah and his concubines at the end of the 19th Century

Nasereddin Shah and his concubines at the end of the 19th Century

As a Monarch, Nasereddin continued the promotion of photography and little by little the subjects changed from the personal to the social and from taking pictures of indoor harems to documenting working class women, wedding parties and family portraits as signs of a modern Iranian society.

After World War II, there was a growing interest in the western cultural world and art institutions and galleries emerged. This period saw a considerable movement to document social and political issues culminating in the documenting of the Revolution of 1979 – when the last Shah was expelled - and its impact on the Iranian society and the eight year war with Iraq.

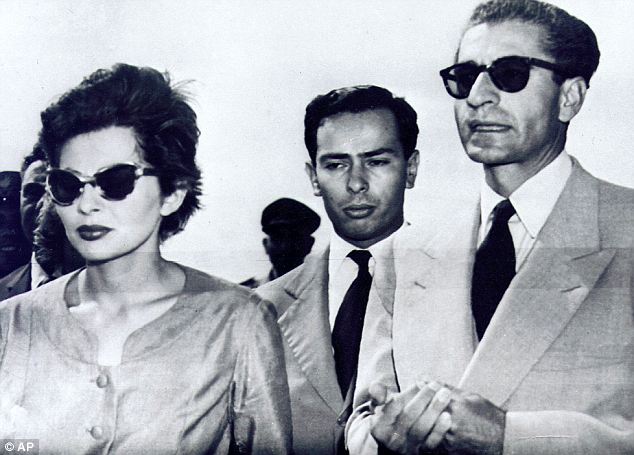

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Queen Soraya Esfandiary

Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and Queen Soraya Esfandiary

Documentary photography became the most important medium for reporting the political situation and the dramatic sociocultural transformation of Iran after the Shah was expelled, the rise to power of Ayatollah Khomeini, the tragedy of war and the socio-political turmoil of the 1980s-90s.

II. Kaveh Golestan, Vali Mahlouji and the “Archeology of the Final Decade”

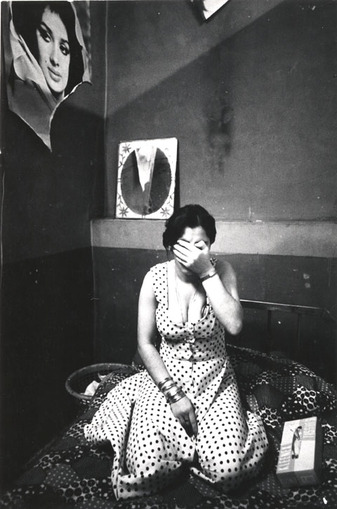

When we were doing our research for the exhibition “Opening Up”, we discovered that the exhibition “The Citadel”, dedicated to the work of Iranian photographer Kaveh Golestan, had been curated by Vali Mahlouji who is also the curator and agent of the Kaveh Golestan Estate. The exhibition, which took place at Foam, the photography museum of Amsterdam, between March and May 2014, included 45 vintage photographs from Golestan’s Prostitute series, which the photographer had taken of the working women of Shahr-e No, the red light district of Tehran between 1975-1977. Mahlouji produced a significant body of documents about the history of the district from the 1920s down to its torching in the final days before the victory of the revolution and its complete destruction and erasure in 1980 which also included the public execution of some of the prostitutes. For more information read Photo London 2015: Kaveh Golestan, Prostitute series.

Courtesy: Kaveh Golestan Estate

We also figured out that Vali Mahlouji was co-curator of the travelling exhibition Unedited History: Iran 1960-2014 at the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris - which my husband and I visited in the summer of 2014 - and later at MAXXI: Museo nazionale delle arti del XX1 secolo in Rome. This well documented exhibition was my first introduction into the world of Iranian contemporary photography in general and the work of Mohsen Rastani and Tahmineh Monzavi in particular.

Curious to know curator Vali Mahlouji himself, I wrote him an email informing him our upcoming show dedicated on Iranian artists and our wish to learn more about contemporary Iranian photography. He was happy to meet us in his apartment in London where he explained that he had set up a research, an educational and curatorial platform called Archaeology of the Final Decade, which aimed to recirculate material that had remained obscure, over-looked, forgotten or destroyed during the last ten years before the revolution. He considered the archive and legacy of Kaveh Golestan an important component of the work of this platform as you can read in The Guardian of March 19, 2015.

Courtesy: Kaveh Golestan Estate

I think we can’t understand Iranian contemporary photography without knowing the story of the black magic box given to the young Prince Nasereddin nor the role of artists like Kaveh Golestan, who besides being one of the founders of street photography was a visionairy artist in the field of surrealist photography and photo-collage. Or, as Sanaz Jamloo points out in Reorient Magazine: “Kaveh Golestan – who was killed on an assignment in Iraq in 2003 when he stepped on a landmine – was a towering figure in the realm of activist journalism. Golestan was an eyewitness to the Iranian Revolution as well as the Iran-Iraq War (1980 – 1988). His photographs not only captured the politically upheavals that radically changed his country into an Islamic republic, but also intimately portrayed a society and people in a time of shockingly rapid transition.” Golestan’s work, although unknown in Europe, has influenced generations of Iranian artists including Rastani and Monzavi.

Courtesy: Kaveh Golestan Estate

Courtesy: Kaveh Golestan Estate

III. From activist journalism to enlightenment: Mohsen Rastani and Tahmineh Monzavi

In the revealing publication Iranian Photography Now (2008, Hatje Cantz) I read the following text written by Mohsen Rastani (1958, Iran): “I am not a photographer, and I do not take pictures for the sake of photography. I came to photography because it enlightens our surroundings better than the eye.” And I started to think: isn’t that exactly what art is all about? Isn’t art the most positive way to enlighten and make us aware of the beauty and the pain that surrounds us?

Courtsey: Mohsen Rastani

From the concubines of Nasereddin Shah, through the prostitues of Golestan to the men and women of Mohsen Rastani (1958) and Tahmineh Monzavi (1988) is quite a long way. In their outstanding work both Iranian photographers examine the lifes of common Iranian families (Rastani) and the complicated situation of young women and transsexuals, prostitutes and drug addicts in Iranian society (Monzavi).

Courtsey: Tahmineh Monzavi

Francis Boeske and I, both convinced of the quality of their work, invited Rastani and Monzavi to participate in the group exhibition Opening Up: 9 Artists from Iran in January 2015. This exhibition marked the opening of Francis Boeske Projects and featured the work of nine emerging Iranian artists (Icy & Sot, Farzad Kohan, Afsoon, Mélodie Hojabar Sadat, Amir Farhad, Azadeh Ghotbi, Newsha Tavakolian) whose work had never been shown to the Dutch audience before. The show was a big event and attracted many visitors. At the request of some visitors of the exhibition, we organized a Q&A between Mohsen Rastani, Afsoon (an Iranian artist, based in London) and myself (in the role of moderator) giving people the opportunity to ask questions and learn more about Iranian photography seen through the eyes of Iranian artists.

Q&A with Mohsen Rastani and Afsoon by Manuela Klerkx

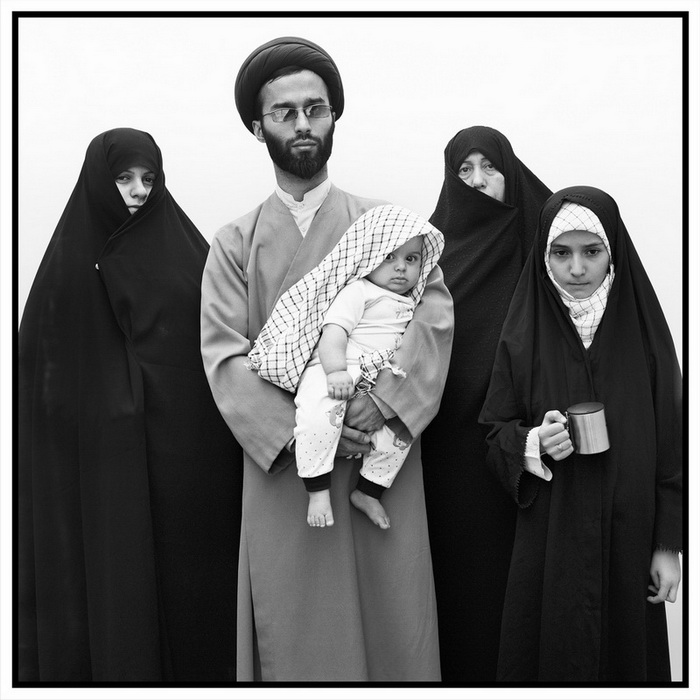

The square, black and white photographs of Mohsen Rastani (for whom we had managed to arrange a visa and who came all the way from Tehran to talk about his life and work) got a lot of attention from the Dutch press. In his work Mohsen isolates people from their surroundings through the use of a white blanket or cloth he installs behind the people he wants to take a picture of. No matter where he is: in the street, on the battlefield or in his studio, he will always bring his white sheet along. Rastani: “We succeed better in looking into other people’s soul and mind, as long as we are not distracted by anything else.” Enlightenment is key.

Interview with Mohsen Rastani, by Arjen Ribbens in NRC Handelsblad, 1 februari 2015

Tahmineh Monzavi is a promising young artist whose work reveals taboos and stereotypes in Iran and Afghanistan through the images of younger women and marginalized people in a rather explicit way.

Courtesy: Tahmineh Monzavi

In the exhibition “Opening Up” we also showed works from the series “All about Me; Nicknamed Queen Maker” in which she points out the deep feelings of womanhood and female dreams.

Courtesy: Tahmineh Monzavi

Monzavi made this series one year after having been emprisoned for one month, an experience that changed her ideas about society in general and the position of women in particular. We are delighted to show new work, made during her recent stay in Afghanistan, at the Amsterdam Photography Fair Unseen.

Courtesy: Tahmineh Monzavi

Source: Sanaz Jamloo, Portrait of a Nation, Reorient Magazine, March 29, 2015

A special thanks to Vali Mahlouji for his editorial advice.

Work by Mohsen Rastani and Tahmineh Monzavi will be on view at Unseen Photo Fair Amsterdam from 18-20 Sept. 2015 at Francis Boeske Projects booth #8.

Check out the website of Klerkx International Art Management.