Is there anything more devastating than the death of one's own child?

Reading or hearing about the grief of (often young) parents makes me sad beyond belief.

On Facebook, parents share their loss, finding comfort - as a friend (who lost his son) poignantly wrote - in 'likes'.

I hope they do. I really do.

The death of Arthur Cave, Nick Cave's son, resulted in two hideous articles in The Times, wherein two reporters insinuated that Cave's obsession with the dark side of life (how can he not be, having lost his father in a car accident at the age of 19?), his specific taste for violent (horror) movies, or the dark corners of the universe, would make him a less responsible parent: I guess their point is that if you raise your kids without fear it makes them more likely to fall of cliffs.

Or drive into trees.

From vultures to ravens - it's a small step.

I recently came across the work of an amazing Japanese photographer: Masahisa Fukase.

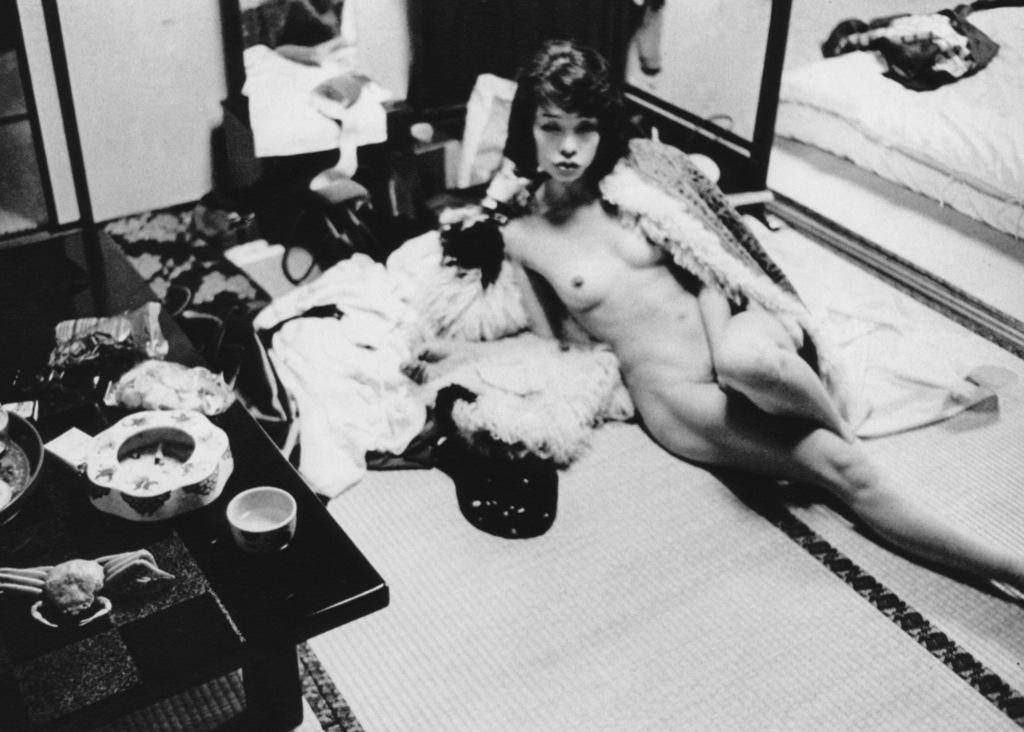

Fukase was obsessed with his (then) second wife, Yoko Wanibe, taking pictures of her all of the time - until she left him, after a relationship which lasted for thirteen years. Fukase was sad beyond belief and returned to the village where he grew up, and while travelling, took an endless amount of photographs of ravens (he did so for years, until, as he once stated, became one himself).

As Sean O'Hagen wrote in The Guardian:

"Fukase's images are grainy, dark and impressionistic. Often, he magnifies his negatives or overexposes them, aiming all the time for mood over technical refinement. He photographs flocks from a distance, and single birds that appear like black silhouettes against grey, wintry skies. They are captured in flight, blurred and ominous, and at rest, perching on telegraph wires, trees, fences and chimneys. Fusake photographs them alive and dead, and maps their shadows in harsh sunlight and their tracks in the snow."

Mourning.

Of lost children, of lost love.

There are currently two shows featuring Masahisa Fukase's work: one in Japan, at the Diesel Gallery (until august 14th), called “The Incurable Egoist,” which is also the title of an article written by Fukase’s ex-wife Yoko for the 1973 supplement to Camera Mainichi. In the article, she states that “The photographs that he took of me unmistakably depicted Fukase himself,” showing that no matter what appeared before Fukase’s lens, he was always looking into himself, using his subjects as way of symbolizing the nature of his existence. The exhibition embraces these words as a cornerstone in presenting a selection of masterpieces and rare unreleased work that Fukase was unable to unveil himself during his decades of silence.

Yoko is also the subject of a fascinating series called "From Window" that Fukase made in 1974. It is currently on show at Les Rencontres d’Arles as part of Another Language, an illuminating group exhibition of eight Japanese photographers curated by the Tate’s Simon Baker. The work has never been shown in Europe before and includes well known photographers like Daido Moriyama and Eikoh Hosoe as well as trailblazing newcomers like Daisuke Yokota and Sakiko Nomura.

Yoko also said about the time they spent together (from 1963 till 1976), that there were moments of “suffocating dullness interspersed by violent and near suicidal flashes of excitement."

Sean O'Hagan, again in The Guardian: "In the show, we see Yoko is a willing participant. She performs, dresses up and poses. The resultant photographs are often joyous as well as sombre. In one portrait, her face is made up to make her look old – she still looks beautiful. In another, taken at the private view for the New Japanese Photography Exhibition, curated by John Szarkowsi at MoMA in 1974, she crouches below his work wearing a kimono as the VIPs pass by, seemingly oblivious to her mischievous presence and unaware that she is a collaborator in the pictures.

When Yoko left him in 1976, Fukase began drinking heavily and suffered bouts of debilitating depression. In the immediate months after her departure, he photographed ravens he saw at train stations on his way home to Hokkaido with the same single-minded intensity that he had photographed her. He continued photographing them until 1982, by which time he was remarried. In Japanese mythology, ravens are disruptive creatures, omens of turbulent times, but here they are symbols of lost love and almost unendurable heartbreak."

Just before his 60th birthday in June of 1992, Masahisa Fukase fell on the stairway of a bar he frequented and suffered a traumatic brain injury. This cruel conclusion to Fukase’s lifelong confrontation with photography also marked the end of all of his creative endeavors in a way that no one could have foreseen. In 2012, twenty years later, Masahisa Fukase passed away without ever making a recovery. Yoko visited him twice a month throughout his long limbo – though, heartbreakingly, he would have been unaware of her presence. “He remains part of my identity,” she said, adding: “With a camera in front of his eye, he could see; not without.”

The allure and enigmatic aura of the works he left behind have yet to fade.

For those who want to find a copy of Fukase's best-known book, Karasu (Ravens), here's some more info: it was shot between 1976 and 1982 in the wake of his divorce to Yakko Wanibe, and during the early period of his marriage to the writer Rika Mikanagi. The photographs were taken in Hokkaido, Kanazawa, and Tokyo. The project is based on an eight-part series for the magazine Camera Mainichi (1976–82) and these photo essays reveal that Fukase experimented with colour film, multiple exposure printing, and narrative text as part of the development of the Karasu concept. Beginning in 1976, exhibitions based on this new body of work brought Fukase widespread recognition in Japan, and subsequently in Europe and the United States. The book was published in 1986 (by Sákyësha) and this original edition of Ravens soon became one of the most respected and sought-after Japanese photobooks of the post-war era. Subsequent editions were published in 1991 (Bedford Arts) and 2008 (Rat Hole Gallery)