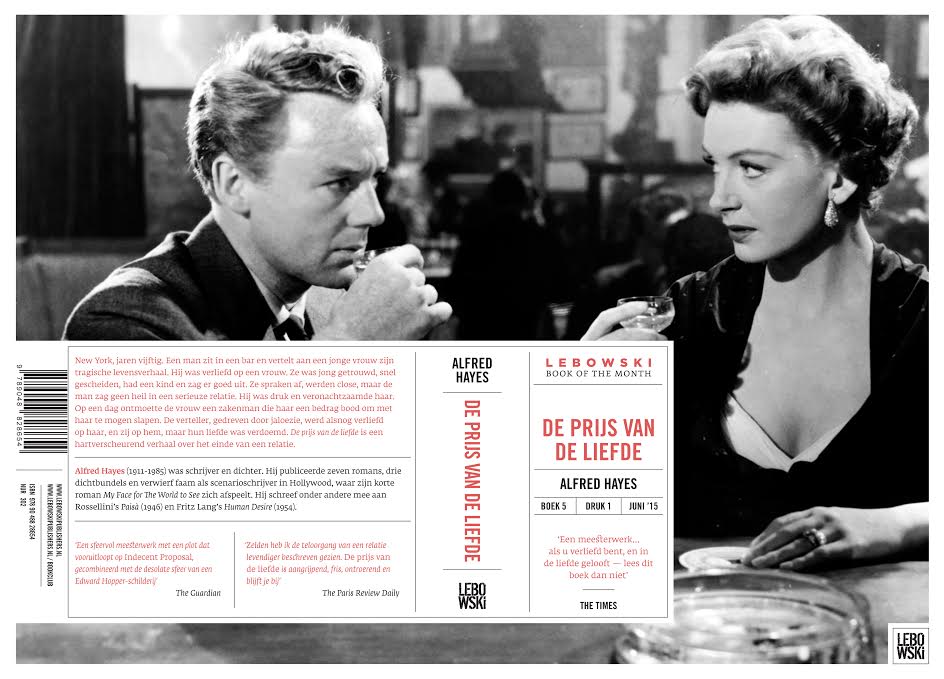

I am re-reading Alfred Hayes' great book In Love, which was recently re-issued by New York Review Books in the USA, and will be published by Lebowski Publishers in Dutch translation (an excellent job done by Marcel Misset) in june 2015, under the title De prijs van de liefde.

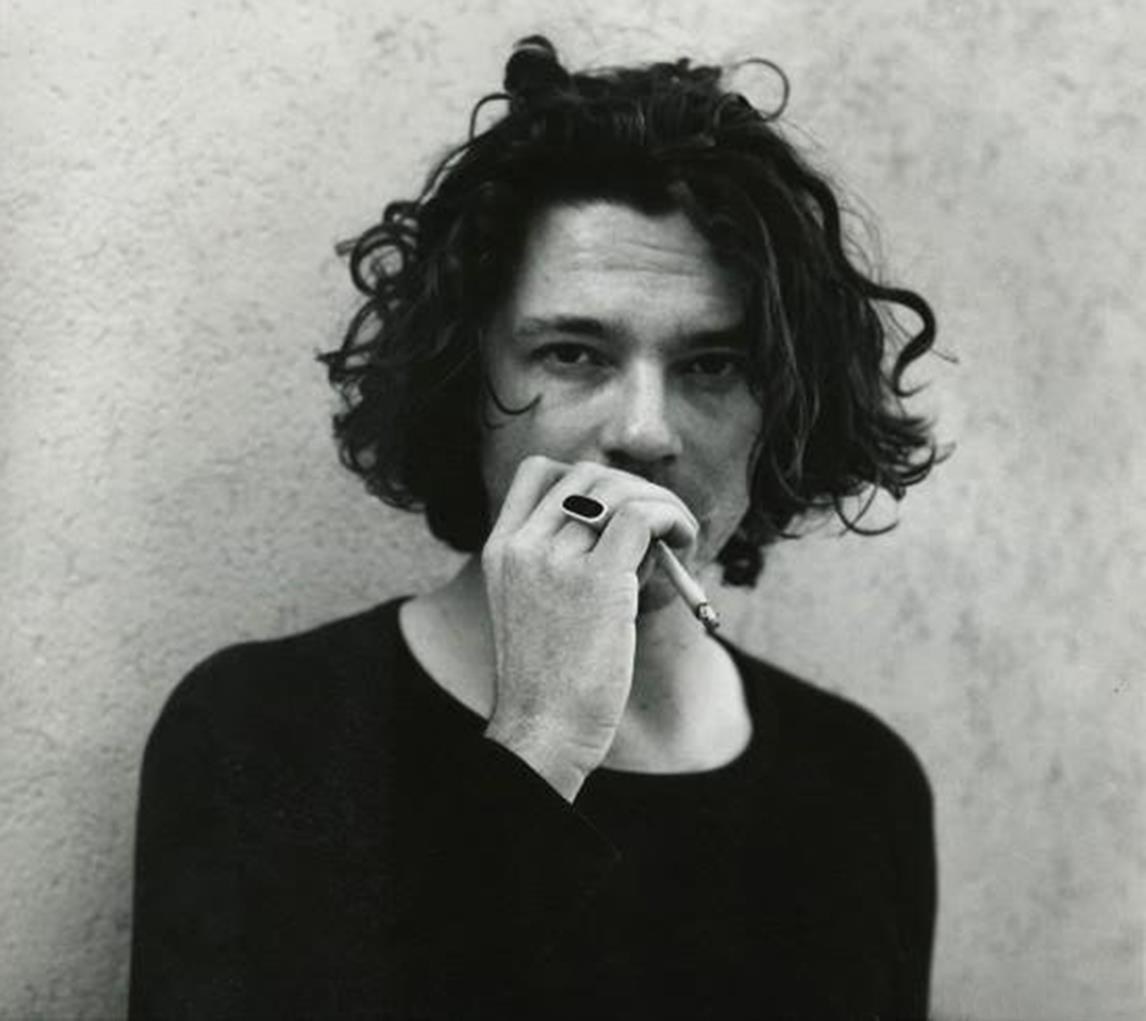

Somehow, the main character of the book reminds me of Michael Hutchence, the former singer of INXS, a band I did not particularly like (although, being a title freak, Elegantly Wasted remains a great title for an album, or a book, or a film), but the singer always intrigued me: a good looking guy, destined to going down (think: Morrison, Cobain). Which he did, in 1997. Some say it was an accident, others call it suicide, and his not so reliable girlfriend at the time, Paula Yates, who overdosed three years after Hutchence, stated his death was due to autoerotic asphyxation (google it). Others just blame Bob Geldof. Hutchence, to me, seems like the kind of guy who, like the main character in In Love, really suffered from being both in and out of love.

The Hayes' book got a great review in The New York Observer and their headline summed it up quite nicely: "The Best Part of Breaking Up: In 1953, Alfred Hayes Published One of the Greatest Books Ever About the End of a Relationship". The review is glowing, and rightly so, praising and commenting that "the beauty of Mr. Hayes’s sentences recreates the often-inexplicable agony that goes with a dying relationship."

I keep reading sentences I want to quote, share, tweet. Is that because I assume this book appeals to experiences every readers must have had, or is it because we, readers (and publishers), want to share our misery just as badly as our happiness? Shame, indecisiveness, fear to commit, jealousy, defeat - it's all there, up for grabs. Just read these sentences:

Of course a woman always seems to choose, with a dismaying instinct, the goddamnest moments to end a love affair. Her dismissals always seem to come the way assassinations do, from the least expected quarter. There will be a note on the kitchen table, propped up against the sugar bowl, on exactly the day when most in love with her you arrive carrying a cellophaned orchid; or walking along the avenue, one arm about her waist, and talking with great enthusiasm about a small house you saw for sale cheap thirty minutes from New York. They seem timed to arrive during birthday parties, when you are apparently happiest, or relaxing in a hot bath, when the house is most peaceful, or taking a short walk in the garden, enjoying what promises to be a beautiful evening. She waits until that precise moment you are bending down to sniff the roses,and thinking that, after all, she is a wonderful girl, and you are really absolutely sold on her, for all the small quarrels and differences, really fine, when bang: she fires from behind the rosebush.

In Love reminds us of the 1993 blockbuster film Indecent Proposal. In Love is also centered around that question: what is the price of love (hence the Dutch title)? But, although this question is one of driving forces in this slim novel, the main attraction of In Love lies in the metafysical observations, the relaxed, laidback way the story is told and unfolds, and the way it hits the nail on the head:

The only thing we haven't lost, I thought, is the ability to suffer. We're fine at suffering. But it's such a noiseless suffering. We never disturb the neighbors with it. We collapse, but we collapse in the most disciplined way. That's us. That's certainly us. The disciplined collapsers.

The prose in In Love, and in it's Hollywood counterpart, My Face For the World to See, is, as The Guardian wrote (calling MFFTWTS a masterpiece) 'very carefully weighted. The sentences, outside the book's dialogue, are packed with commas and careful qualifications, the way you would write if you wanted to make sure that every possibility of nuance or interpretation had been scrupulously attended to.'

Alfred Hayes was also a famed scriptwriter. He was co-writer (alongside Klaus Mann and Federico Fellini!) on Roberto Rossellini's Paisan (1946), for which he was nominated for an Academy Award; he received another Academy Award nomination for Teresa (1951). He adapted his own novel The Girl on the Via Flaminia into a play; in 1953it was adapted into a French-language film Un acte d'amour.

He was an uncredited co-writer of Vittorio De Sica's neorealist film Bicycle Thieves (1948) for which he also wrote the English language subtitles. Among his U.S. filmwriting credits are The Lusty Men (1952, directed by Nicholas Ray) and the film adaptation of the Maxwell Anderson/Kurt Weill musical Lost in the Stars(1974). His credits as a television scriptwriter included scripts for American series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, The Twilight Zone, Nero Wolfe and Mannix.

Back to In Love. As Michel Houellebecq once said, in The Elementary Particles: “Love binds, and it binds forever. Good binds while evil unravels. Separation is another word for evil; it is also another word for deceit.” Disciplined collapsers, that's what we are.