On Sturtevant, the mother of appropriation art (and a bit on Houellebecq)

Last week, I went to see the Sturtevant exhibition in the Madre Museum in Napels. While walking around – enjoying the art, the videos, the witty texts – I had to think of Houellebecq and his bon mot that ‘anything can happen in life, especially nothing’. I love Houellebecq’s novels, especially Platform and, mostly, Whatever, but there is, of course, one novel in which he deals with art (and the position of artists in the world): The Map and the Territory. According to Houellebecq an artist is ‘someone who is constantly bored’, meaning: an artist seeks refuge in the world of art because he can’t deal with the real world: “Those who love life do not read. Nor do they go to the movies, actually. No matter what might be said, access to the artistic universe is more or less entirely the preserve of those who are a little fed up with the world.” (from his first book H.P. Lovecraft: Against the World, Against Life)

In The Map and the Territory (2010), artist Jed Martin, his main protaganist, makes his name by photographing Michelin road maps and superimposing concrete images from the territory covered by the maps onto the photographs:

It was then, unfolding the map, while standing by the cellophane-wrapped sandwiches, that he had his second great aesthetic revelation. This map was sublime. Overcome, he began to tremble in front of the food display. Never had he contemplated an object as magnificent, as rich in emotion and meaning, as this 1/150,000-scale Michelin map of the Creuse and the Haute-Vienne. The essence of modernity, of scientific and technical apprehension of the world, was here combined with the essence of animal life. The drawing was complex and beautiful, absolutely clear, using only a small palette of colors. But in each of the hamlets and villages, represented according to their importance, you felt the thrill, the appeal, of human lives, of dozens and hundreds of souls — some destined for damnation, others for eternal life.

In the novel Houellebecq clearly pokes fun at conceptual art, but he also points out that art can solve a problem: money can make artists rich, making it possible for them to disappear from reality.

The circle is completed.

Would Houellebecq appreciate the works of Elaine Sturtevant? I am inclined to answer: yes.

Houellebecq wrote about the subject of cloning in The Possibility of an Island, and Sturtevant is exactly about that: she reproduces work of other artists, making them her own – in her case, by altering small details (size, image), making each copy unique.

A great paradox.

From the obituary in The New York Times:

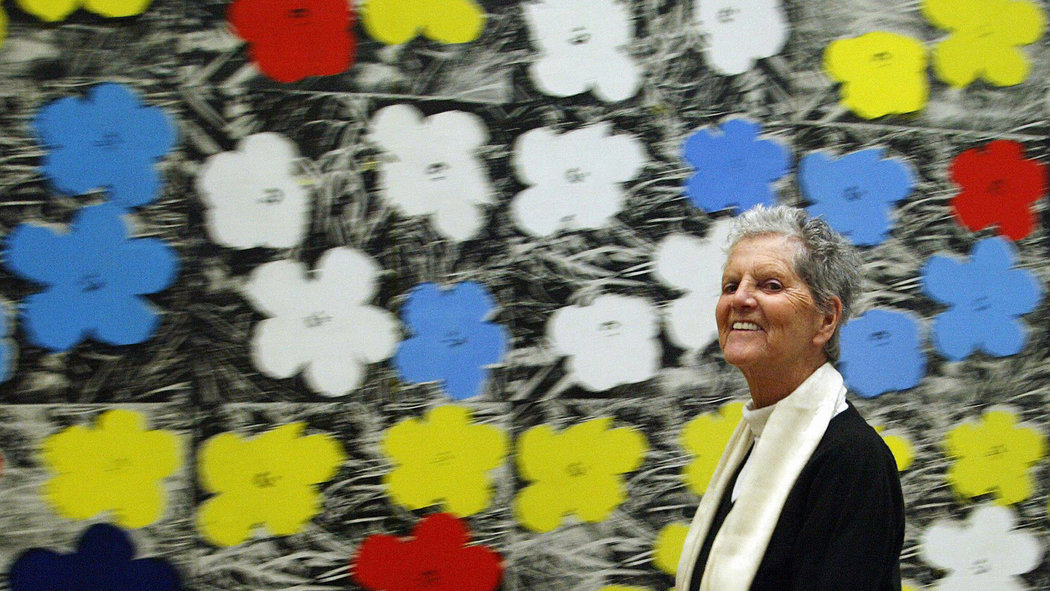

“Elaine Sturtevant (1924-2014) was an American conceptual artist who had her first show at the Bianchini Gallery in New York in 1965, which featured, among other pieces, a George Segal-like sculpture, silk-screens à la Warhol’s “Flowers” series (an obliging Warhol helped Ms. Sturtevant make them by lending her his original screen) and an ersatz Stella. In that show, and in her subsequent work, Ms. Sturtevant tacitly asked: When is a Warhol not a Warhol? When is it one — and what makes it so? One answer, her art suggested, lay in the prototypes, which were, per the artistic preoccupations of the day, often copies themselves. (Think of Warhol’s soup cans.) If one borrows an image that is itself borrowed, her work suggested, then perhaps neither is truly original.

Ms. Sturtevant, known professionally simply as Sturtevant, was no forger. She was sometimes called the mother of appropriation art: the movement, which flourished in the 1980s and afterward, that makes new artworks by reproducing old ones. But with characteristic bluntness, she disdained the term, preferring to call her working method “repetition.”

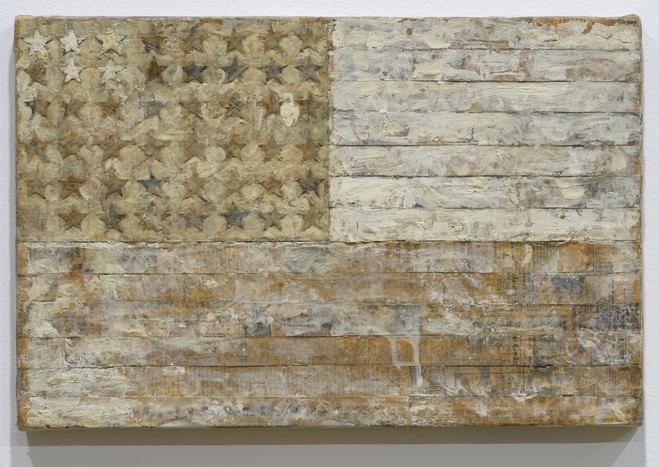

As a replicator, Ms. Sturtevant was an original. A Sturtevant work is as instantly and uncannily recognizable as a Warhol silk-screen, say, or a Johns flag. But, at the same time, each in its own way is a deliberately inexact likeness of its more famous progenitor.

By holding up her imprecise mirror to a gallery of 20th-century titans, Ms. Sturtevant spent her career exploring ideas of authenticity, iconicity and the making of artistic celebrity; the waxing and waning of the public appetite for styles like Pop and Minimalism; and, ultimately, the nature of the creative process itself.

In the beginning, Ms. Sturtevant’s work was praised for its wit, sly humor and desire to expose viewers to a blizzard of epistemological questions. “I create vertigo,” she liked to say.

Where Warhol had been sympathetic to her aims (queried about his silk-screening method, he was reported to have said: “I don’t know. Ask Elaine”), other artists were less so.

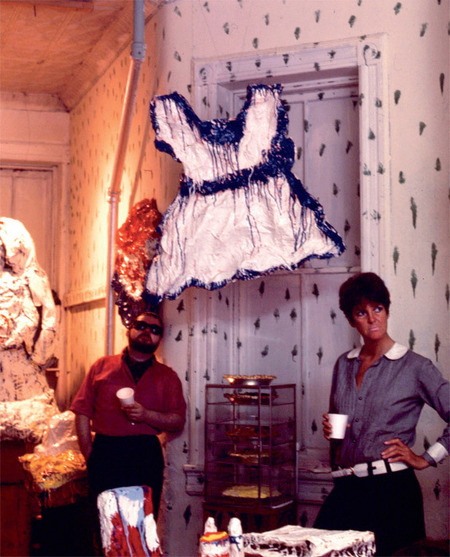

When, in 1967, just blocks from where the original had stood, Ms. Sturtevant opened her version of Claes Oldenburg’s “The Store” — a pop-up emporium featuring sculptures of ordinary objects he had erected a few years earlier on the Lower East Side of Manhattan — Mr. Oldenburg was not amused.

(Sturtevant (right) at her The Store of Claes Oldenburg, 623 East Ninth Street, New York, 1967. Photo: Virginia Dwan)

“Oldenburg is ready to kill me,” Ms. Sturtevant told Time magazine in 1969. “It all makes him dive up a wall.”

Over time, critical consensus turned against her, and Ms. Sturtevant withdrew from the New York art scene. She produced little from the mid-1970s to the mid-80s, re-emerging in 1986 with a show at White Columns, the alternative art space in Lower Manhattan.

Though she freely inhabited the artistic skins of others, Ms. Sturtevant took immense pains to obscure the particulars of her own history. Early in her career, she shed her given name like so much distracting baggage; to the end of her life, she countered interviewers’ biographical queries with a two-word response — “Dumb question” — insisting they focus on the work alone.

In recent years, Ms. Sturtevant worked increasingly in video, producing installations — some incorporating footage shot directly off her television set — that bemoan what she saw as the deracinated human condition in the age of digital reproduction.”

In 2007, an original “Crying Girl” by Lichtenstein — to the extent that one print in an edition of identical prints can be called an original — sold at auction for $78,400. In 2011, Ms. Sturtevant’s canvas reworking of “Crying Girl” — the only Sturtevant painting of its kind in existence — sold for $710,500.” In 2014, Frighten Girl was auctioned again, at Christies, for $3.413.000.

In Lichtenstein, Frighten Girl, Sturtevant created a painting after one of Lichtenstein’s famous depictions of distressed women, in this case, Crying Girl. Lichtenstein’s version is a lithograph and was printed in 1963, but Sturtevant has rendered her woman in oil and graphite on canvas and in a much larger size. Differences aside, Sturtevant’s painting is strikingly similar to Lichtenstein’s print, from the color palette employed to the cropping of the figure, the style of the line and the use of Ben-Day dots on her skin. Sturtevant’s work is not, however, an exact replica of the source artworks she selects. In Lichtenstein, Frighten Girl, Sturtevant has made calculated, if somewhat cryptic, changes: her female figure has bright blue eyes, part of the background is red instead of black and some of the detail lines in the hair and around the nose have been altered. One aspect that remains the same, though, is the emotional intensity and drama conveyed by both Girls with their wind-blown flaxen locks, plump cherry-red lips and matching nails and large glittering tears. The consummate embodiment of tragedy, Sturtevant’s woman expresses heartrending anguish, fear and panic with her eyes perpetually locked on the viewer.

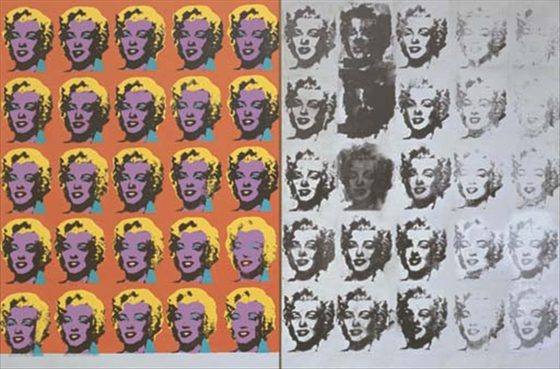

The current auction record for a Sturtevant work is a “Warhol Diptych” from 1973, which was auctioned in may 2015, again at Christies, for a whopping $5.093.000

(Warhol Dyptich, 1973)

Anything can happen in life, especially nothing.

What is more ‘nothing’ than living the life of someone else?

I find it fascinating that an artist that can dedicate a major part of his/her working life exclusively to other artists.

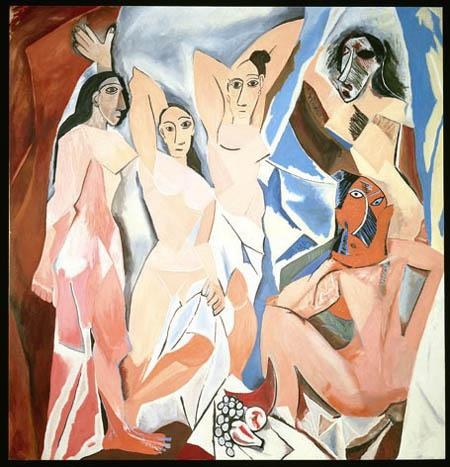

Appropriation art goes back to the 1910s, when Picasso and Bracque ‘used’ common objects (bottles, newspapers) in their paintings. Then Duchamp came along, with his ready mades, then Dada (collages, cut ups), then the surrealists joined in, all the way to fluxus and pop art (advertizing, commodities, mass production) in the sixties.

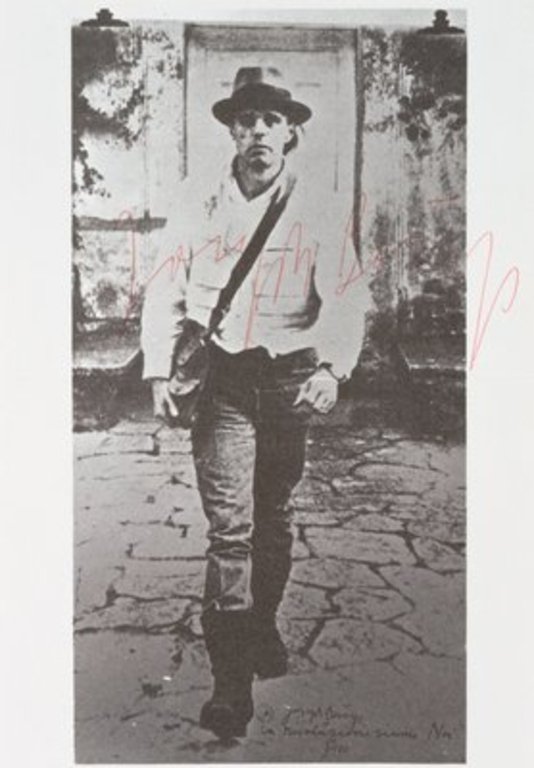

But no one, before Sturtevant, took it to the next level: from 1964 on she “repeated” the works of some of the most iconic artists who were her contemporaries (from Marcel Duchamp to Joseph Beuys, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Frank Stella, all the way up (in the eighties) to Paul McCarthy, Mike Kelley, Robert Gober, Anselm Kiefer and FeÌlix GonzaÌlez-Torres, to name only few). In this she was well ahead of her time in exploring concepts such as “authorship” and “originality” in relation to the mechanisms of production, circulation, reception and canonization of contemporary artistic imagery and imagination.

(Joseph Beuys, The Revolution is Us, 1972)

(Sturtevant, The Revolution is Us)

In her manual repetition from memory, for example, of Duchamp’s Nue descendant un escalier or Fresh Widow, of Beuys’s The Revolution is Us or his performative actions, of Warhol’s Flowers, Marilyns or Silver Pillows, of Oldenburg’s Store Objects, Johns’s flags, numbers and letters, Lichtenstein’s paintings inspired by graphic comics, Stella’s minimalist and post-painterly abstraction and Gober’s Partially Buried Sinks (a true sampling of Conceptual and Pop Art, with their various authors, who since the mid-sixties have also presented significant exhibitions and cycles of works in Naples, as in the case of Beuys or Warhol), Sturtevant set at the center of her research the issue of the autonomy of art, of difference, of a critical relationship to art and to its media and signifying context. It should be noted in this respect that Sturtevant almost exclusively referenced artists contemporary to her, with effects of simultaneity between the work and its often disquieting repetition. An aesthetic and intellectual research that short-circuited the logic of Pop Art itself and superseded the criteria of the languages of Appropriation, which emerged later in the eighties, and which the artist not only anticipated, but from which she differed by the deep roots of her practice in the thinking of the twentieth- century philosophers of difference (from Michel Foucault to Gilles Deleuze), going so far as to foreshadow, in her analysis of the power of art and images, the impact of cybernetics, the principles of cloning and the scenarios of the digital sensibility, opening the door to the realm of the simulacrum and its simultaneous contemporary dissemination.

But what particularly concerned Sturtevant was the reversal of values and hierarchies of reality and its artistic representations, in which Warhol’s becoming a machine, his serial and superficial codes, “reflect our cyberworld of excess, of fetters, transgression, and dilapidation,” which absorbs reality without suppressing it. In this respect, the central axis of Sturtevant’s production is to be found precisely in two key XX century figures: on the one hand Andy Warhol, whose logic Sturtevant is perhaps the only artist to have completed and taken to its extreme conclusions, and the other Marcel Duchamp. The logic of Duchamp, in particular, in his condemnation of taste as the interdiction of the word and the immobilization of thought, guided Sturtevant in her critical selection of artists and works to which she turned her attention, indifferent to biographical criteria, groupings or aesthetic coherence, being concerned rather to plumb the deep structure of the artwork, its “real power,” the intensity and the energy of the invention of every form and image. From this emerges an idea of contemporariness as something which precludes chronological criteria or adherence to a context that transcends its contingent time: the Duchampian revolution, which Sturtevant again is one of the few artists to have fully grasped, lies not in its conceptual articulation in objects, but in its revolutionary leaps of meaning or its resistance to common sense, and therefore its lack of interest in the pursuit of creativity, novelty and recognition by the art world in favor of indifference towards them and the sabotaging of the notion of the work of art itself, unique and authentic.

Mike Bidlo more or less ‘copied’ Sturtevant in the eighties, with his “not” series: Not Warhol, Not Picasso, Not Pollock etc. Bidlo painstakingly copied these artists works. In 1984, he recreated Warhol’s Factory, and in 1988 he exhibited 80 copies of Picasso’s paintings of women. Using only reproductions for reference, Bidlo creates exact replicas of his chosen subject. Many of his works are free-hand drawings, devoid of color.

After Bidlo came Sherri Levine, Richard Prince, Jeff Koons, Rob Scholte, Servaas and business art.

(Rob Scholte, Copyright)

Back to Sturtevant.

What’s also quite amazing about her work is her exquisite taste: she reproduced works by artists who are now all household names, but back in the mid sixties were often just starting out. In that sense she operates as a scout (or gallerist): she had a fine nose for picking out the right names.

In the early 1970s, Sturtevant stopped exhibiting art for more than 10 years.

From the early 1980s on, as mentioned already, she focused on the next generation of artists, including Gober, Kiefer, McCarthy and Gonzalez-Torres.

In 1991, Sturtevant presented an entire show consisting of her repetition of Warhol’s ‘Flowers’ series.

(Sturtevant in Moderna Museet)

Her later works mainly focus on reproductions in the digital age. Sturtevant commented on her work at her 2012 retrospective Sturtevant: Image over Image at the Moderna Museet: “What is currently compelling is our pervasive cybernetic mode, which plunks copyright into mythology, makes origins a romantic notion, and pushes creativity outside the self. Remake, reuse, reassemble, recombine – that’s the way to go.”

(Sturtevant, Sex Dolls, 2011; installation view, Sturtevant: Leaps Jumps and Bumps, 2013; Courtesy Serpentine Gallery, London. Photo: Jerry Hardman-Jones)

Sturtevant Sturtevant runs till 21 september 2015 in Museo Madre, Via Settembrini 79, Napoli.