Hugo Kaagman is a true stencil pioneer, probably the first stencil artist in Europe (in the text below he states that he made his first stencil in 1978, meaning he had stencils out long before Blek le Rat got busy in France). In the USA, John Fekner allready put stencils out in the streets in 1976, but these were texts only, contextualizing the environment. Hugo has got it all: punk, reaggae, politics, geometric patterns, humor - and a great sense of colour.

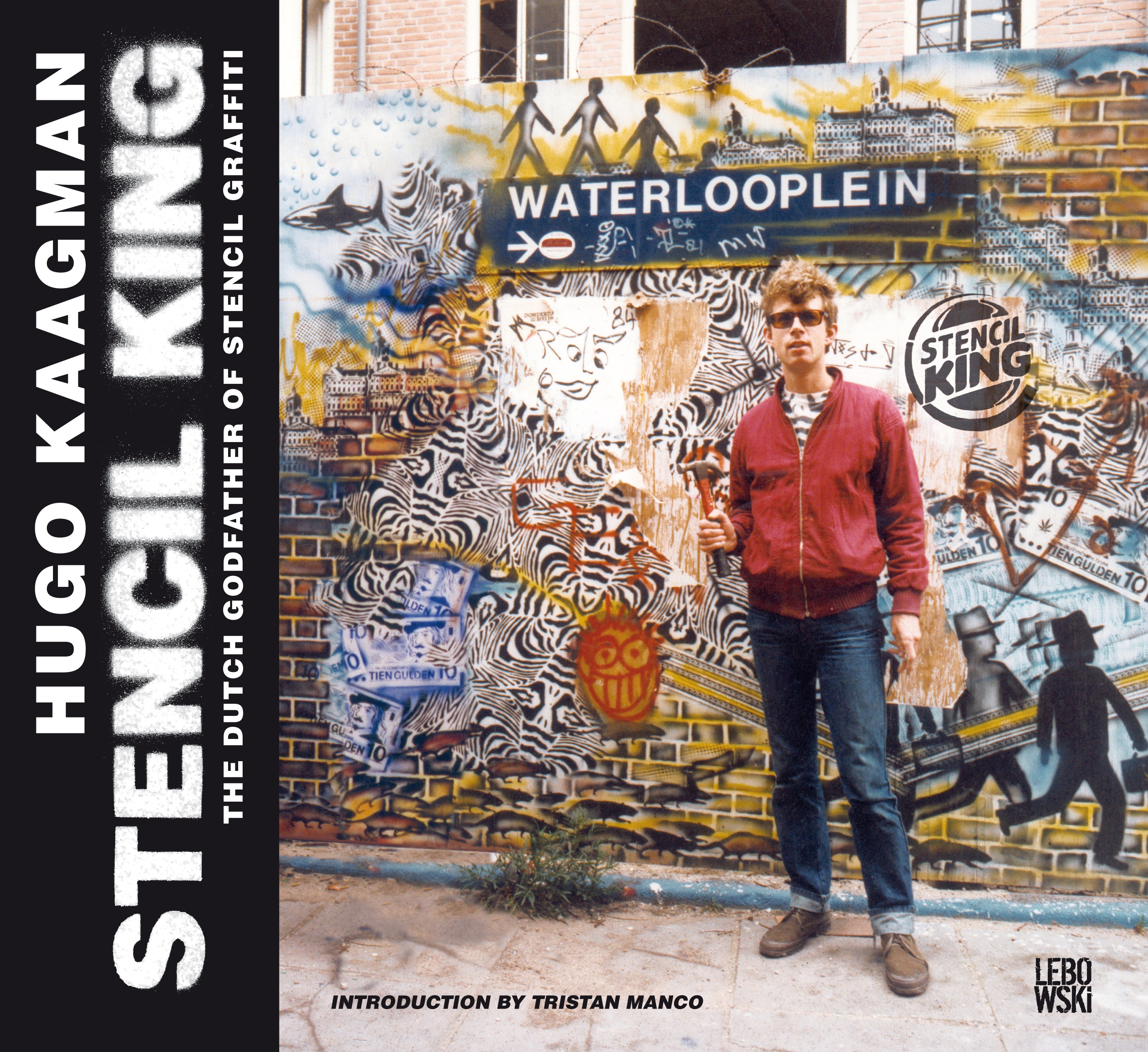

I have collected some of his early stencil works and had the pleasure of making a great book book with him: Stencil King, which was published in 2009 by Lebowski Publishers. I interviewed Hugo, asking him about his artistic roots, his love for Africa, for punk, for the do it yourself movement. I transcribed the interviews, and turned them into four 'prose poems', each dedicated to one of the decades he has been been active in: from the seventies up till 2010. I am still happy with the result; reading the texts now, six years after, they still evoke Hugo's mindset. EIGHTIES ‘After DDT (1978) came gallery Anus (1979), came gallery Ozon (1980), came gallery Zebra (1981).

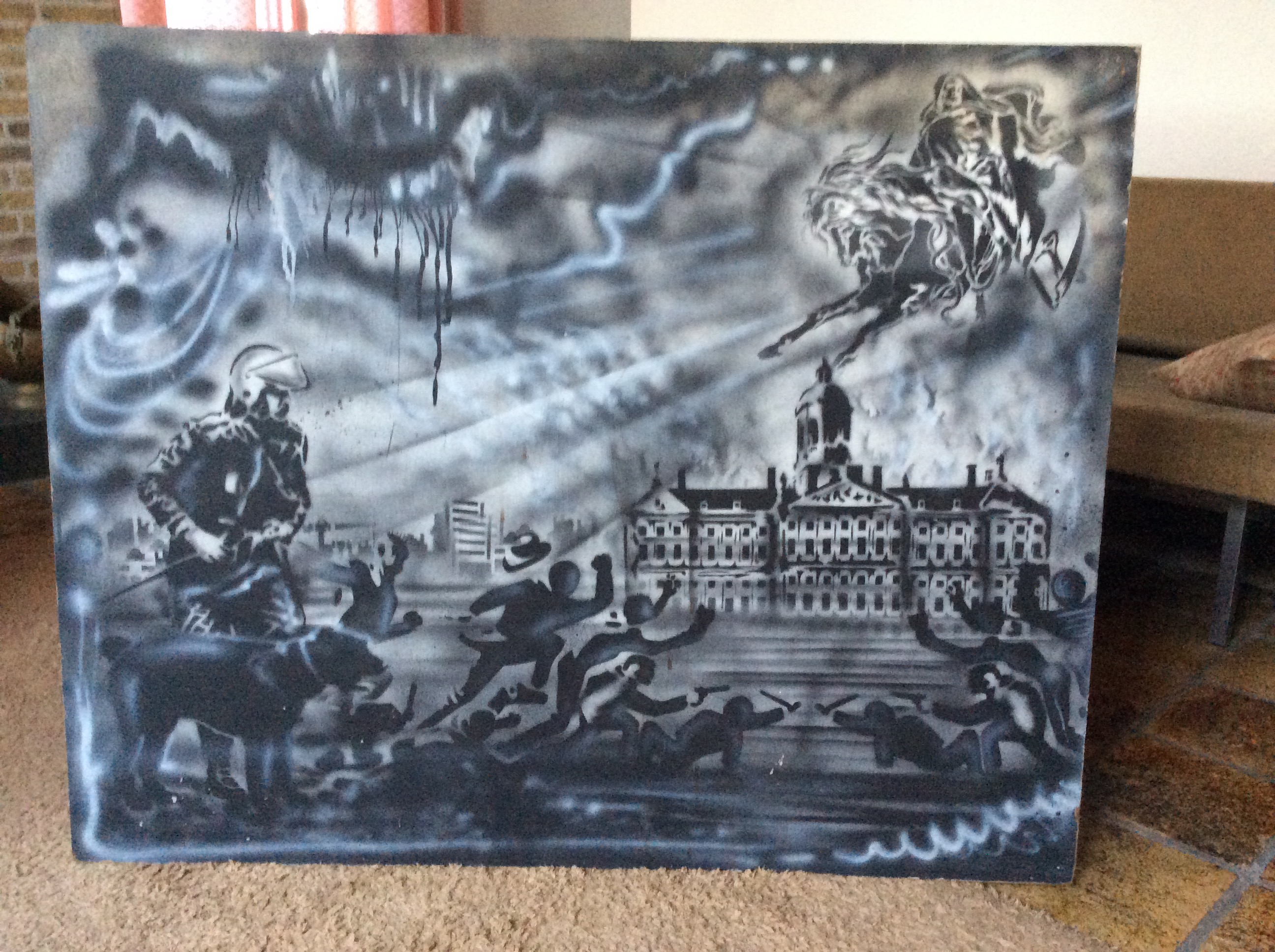

Aorta was also founded in 1980. Riots at the crowning of Beatrix. The city was on fire. Apocalypse.

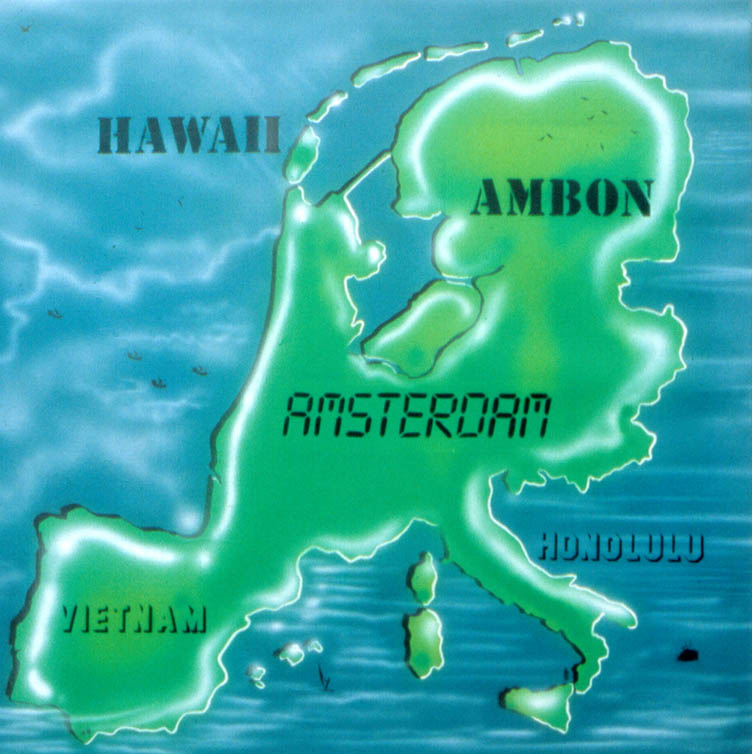

Punk was past its prime in 1981-1983, it was followed by New Wave. And then of course came 1984: the Orwellian vision of the police state. In 1984-1985 New Wave gave way to yuppiedom, the advent of pragmatism. Nobody was doing well. In 1983 I made a legalised fence mural on Waterlooplein, a KoeCrandt on panels, sixty metres of political and social commentary, Arabic patterns, zebra motifs.

In 1985 I was commissioned to work on the Transvaal tunnel near the Parool building. Damn. Another city gate.

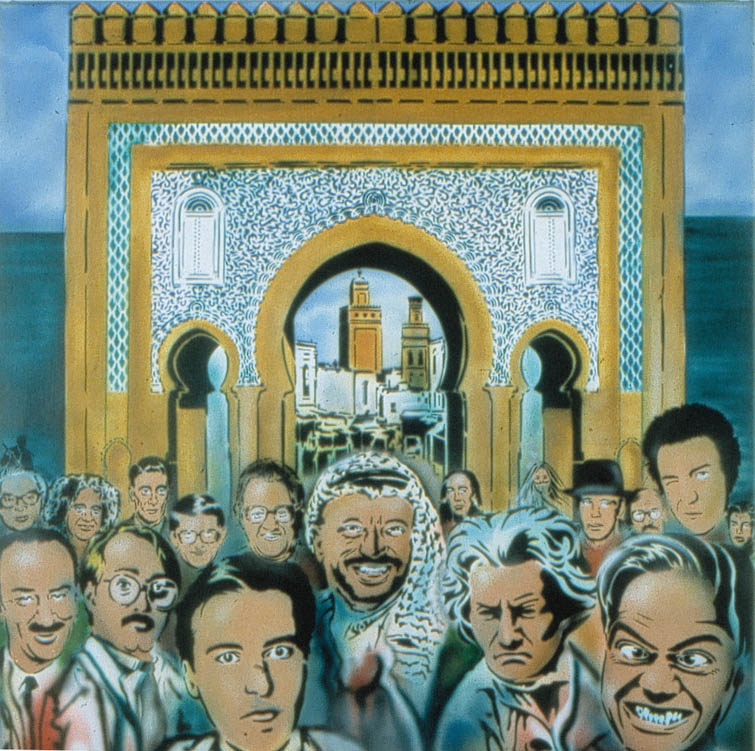

I thought to myself: now I’ve evolved from ideologist to artist, and I’ve found my means of expression. The collage. I could put more into that than I could in the writing. I became a paperless ideologist. I used the ornaments and patterns as the source, the frame, and I merged that with the beauty of tradition. To that I added contemporary issues and topics.

Those commissions allowed me to find my niche, and I alternated that work with illegal stuff. In 1984 the rise of American graffiti was a fact. In his gallery, Yaki Kornblit had people signed up on waiting lists to buy those works. They sold like mad. Big pieces throughout the city. 1985 came around: hip hop culture – this is the music, this is the dance and this is the art. In your face.

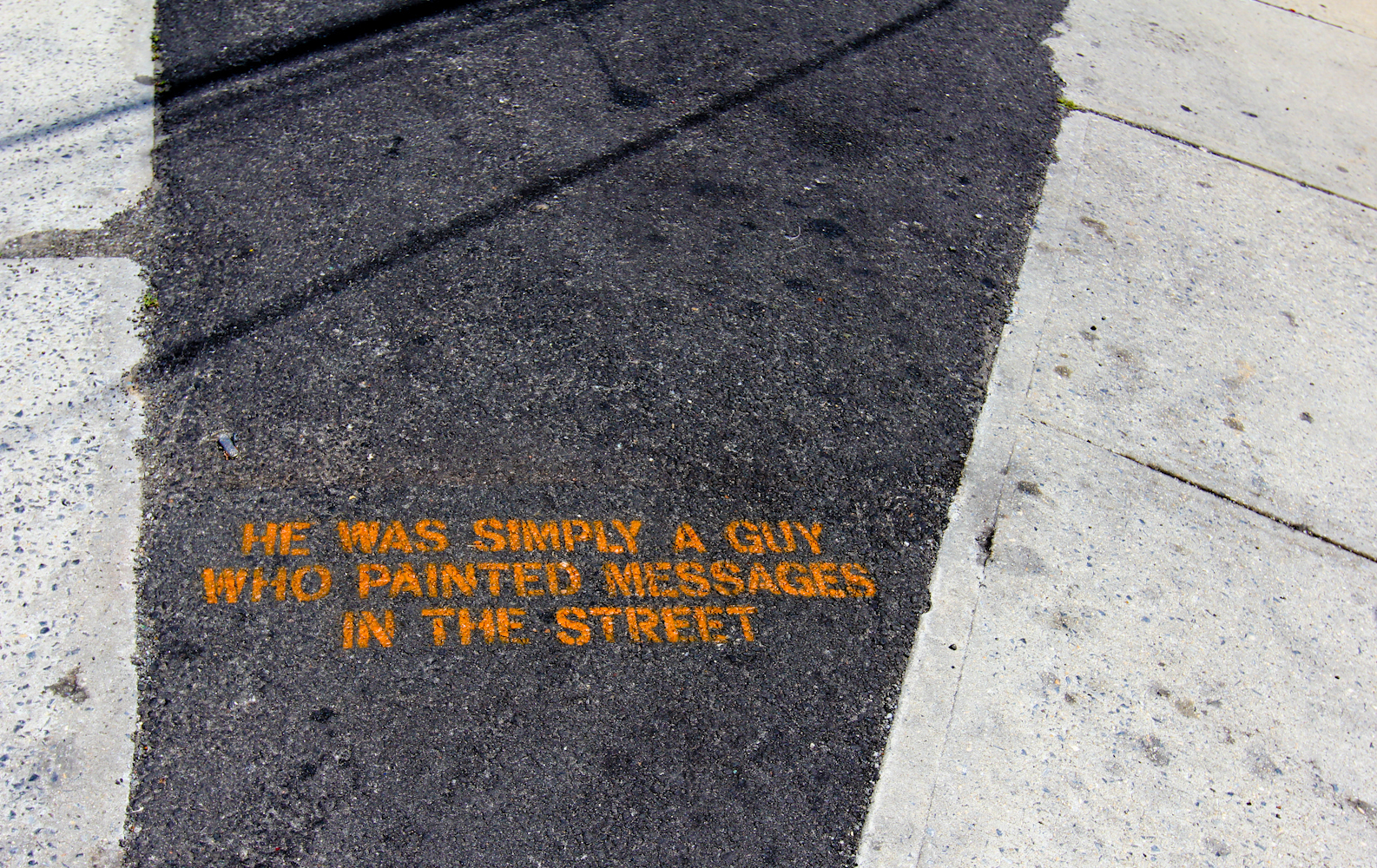

The rise of the United Street Artists in Amsterdam. Shoe. Delta. High. Joker. Jaz. They didn’t give a toss about delivering a message. Messages were for answering machines.

Bubble letters and wild style became popular, that gave the whole deal a push forward, I liked wild style, that turns it into art. Legible letters were too much of an ego trip to my taste. In 1986 the media declared graffiti dead; USA quit, became an advertising agency. Graffiti didn’t generate much of an income you see, and a lot of those Americans went back to their paper routes. Between 1985 and 1990 I started to paint on canvas, in a studio. I felt a kinship with Rob Scholte, his views on post-modernism, copyright, how everything’s been done, and that there’s nothing you’re not allowed to use.

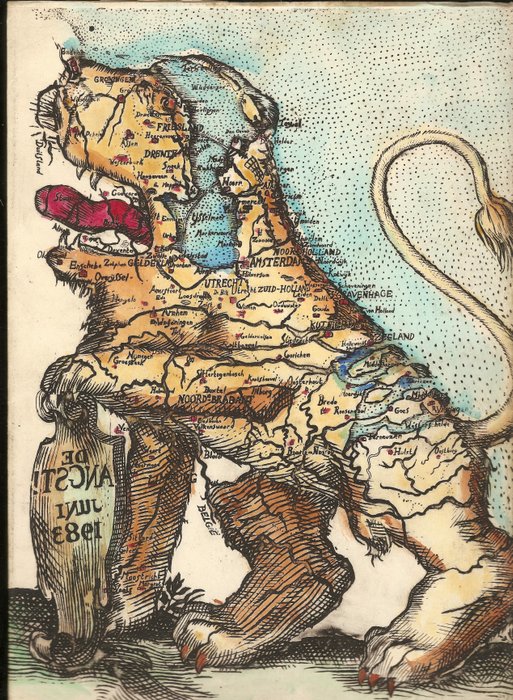

(Rob Scholte, De Angst, 1983) That’s an especially useful concept when you work with stencils. He was a man with a definite noetic gravity, and his attitude appealed to me – not a brush stroke, but the intellectual approach. He played the money game, he preceded Jef Koons in that respect. Art’s no good until it sells. Business art. It all relates back to Warhol - anything can be art.

The art world in the Netherlands – don’t forget that yuppies had entered the arena – ran parallel to New York. And so, everybody wanted to own art, it was a status symbol, things were positively brimming over, there was massive attention in the media, there was loads of money, we sold a lot. I held my first exhibition in 1988 at The Living Room, which was the hottest gallery back then. I showed predominantly abstract works with patterns. According to the gallery, the days of Rasta and punk were over, all they cared about was what they could sell. I was introduced to the official art world, with its trendsetters, the policy makers, the coke snorters. I didn’t know the lay of the land, but I wanted to belong, I wanted to push forward, I wanted to put my mark on society, because although you can accomplish a lot from down on the streets, you really do need the cultural elite. Or so I thought. I learned an important lesson: what you don’t say can’t be used against you. And that’s how things went until the first Gulf War in 1992. But for me personally, the eighties came to their definitive end in 1994, with the attempt on Rob Scholte’s life.’

Stencil King was published by Lebowski Publishers in 2009. For the book I interviewed Hugo, and wrote four texts: about Hugo in the seventies, eighties, ninetees and zeros. The texts were written in Dutch and translated into English by Judith van der Wiel. Tristan Manco wrote a great introduction: From Waterloo Square to Waterloo Station, referring to Hugo's monumental work made on many wooden panels around Waterloo Square in Amsterdam in the early 80ties, till the invite by Banksy, to create work at Waterloo Station (Leake Street) in London, in 2008. Other posts: 70: http://www.oscarvangelderen.nl/art/hugo-kaagman-stencil-king-seventies/ 90: http://www.oscarvangelderen.nl/books/painting-the-sky-on-hugo-kaagman-stencil-king-nineties/ 00: http://www.oscarvangelderen.nl/art/from-waterloo-square-to-waterloo-station-thanks-to-banksy-on-hugo-kaagman-stencil-king-zeros/